Solve problems where they are (not where you are)

How generalists can advance in a specialist's world

Recently, while spending time with the members of the Health Tech Nerds community on the clinicoproduct divide (thanks Kevin & Abbey for hosting!), we surfaced the timeless question of what to do when a problem in your organization falls outside of your zone of control. This inevitable challenge occurs as an organization increases in complexity, and tends to break hardest on Directors or VPs with enough authority to recognize the problem, but lacking the position power to address the issue without being ignored or attacked by the offending functions. Fearing the powerless fate of mythical Cassandra caused many to feel that the only choices were to:

Control what you can control while accepting what you cannot

Influence where the problem lies

Identify the situation as impossible and then quit

Sullen nods in the conversation suggested everyone had tried one or all of these options. Choice 2 is obviously the “right” answer, but many felt as though this were unlikely due to the externalized factors of organizational power dynamics, leadership biases, expectations for behavior by gender roles, and/or personal or career risk from “pushing too hard.” These are all very real fears. In certain organizations attempting to fix problems outside of your domain will draw the ire of others who will immediately point out any problems within your domain, especially when their inaction is causing them.

Sometimes life gives you perfectly concrete examples: A mentor of mine asked me to speak with his nephew who had taken a role managing a snack manufacturing plant, potato chips, corn chips and the like. As a shift manager for bagging and weighing, he was evaluated on “grams given” a measure of how many extra chips make it into the bag. He decried that his team tried everything to fix the problem, but casually remarked in chip jargon that there were “too many chips coming over the wall” referring to the previous flavoring step, managed by a different team with different leadership. I couldn’t help but laugh as the next words out of my mouth were, “you are going to have to go over the wall” to solve this problem. Although his team was not causing the problem, the set up of the managerial lines and metrics of the organization meant that they were only being punished for it. Sound familiar? He immediately jumped in with the standard rebuttals: “That’s not my department. I can only control what I can control! How do I get somebody else to do their job?”

Organizations are tightly-linked complex entities, often divided by functional area as though the customer, product or problems care about what you name your department. Solving problems cross-functionally, not merely identifying them, is crucial for navigating complexity, and your ability to do so is the demarcation between the Interpreter and Integrator phase of your generalist career. Generalists will be the first to spot these problems, those least able to stay in their corner, and the ones who will be most rewarded for figuring them out, punished for upsetting the apple cart, or both!

If major career advancement is not enough motivation, as long as you still share the company mission as your own, you must find your courage, overcome your fear of resistance and reprisal. If you are willing to quit for what you believe in, you should be willing to get fired for what you believe in. Most fears of being fired for attempting to improve the company, albeit stepping on toes while doing so, are generally overblown. Also, if you get fired without cause (don’t do anything to get fired with cause…), then they are likely going to pay you something in severance, so all things considered the slightly better financial outcome is to get fired. The purpose here is not to condone reckless behavior, but rather for you to imagine yourself in jeopardy, so that you summon your courage to act in favor of your beliefs, while reducing your fear of the consequences that impede action.

So why not simply control what you can, fixing all of the problems within your sphere before bothering others? Your counterparts will not hesitate to point this out when you come sniffing around their domain. The answer is no, and their false equivalence aside, the reason why fixing non-constraint problems in your organization is meaningless is the same reason as rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic was meaningless–because the constraint is not (no longer) within your domain. The constraint does not care about your org chart. Constraints move all the time, ironically due to previous changes and fixes. If the constraint were in your domain, you would have already fixed it, and doing so would generally mean that the constraint shifts out of your domain. This is a natural consequence of interconnected complexity. As soon as you figure this out, you must redouble your courage to go wherever the problem is, but only if you’d like to solve it.

The challenge is that the moment you start looking outside of your domain, you can expect to find… resistance. The resistance will come in many forms, but generally resolves into denial and defensiveness. Basically there either is no problem OR it is not my fault. To approach problems like these, you will have to tackle both, but today let’s focus on denial– is your problem really a problem?

If you’ve heard the phrase “where there’s a will, there’s a way,” the inverse is even more true: “Where there is no will, there is no way.” If you want to solve a problem you must first convince others both that it exists and that it matters. Your best bet is to assume you are wrong, that there is no problem, and go about understanding the situation with empathy. There are tools such as the 5 Whys, Root Cause Analysis that may help frame your approach to diagnosing problems. If you follow a disciplined, curious approach, you are likely to hone in on the source of the problem you’ve uncovered, be it too many chips in a bag, slowly shipping terrible software, not improving clinical outcomes or simply losing more money over time.

As you approach the source of your problem, before your instinct to fix it, to diffuse denial and defensiveness you must understand the context that created the problem in the first place. Your cause will inevitably stem from a previous senior leadership decision, or lack thereof. Unfortunately, all sins of a company are sins of senior leadership. It is not an easy job to do well.

If you are lucky enough to find that your current problem stems from an actual, intentional managerial decision, then your next step is to confirm that the facts and circumstances that generated that decision are still accurate. If so, then your problem is a symptom or waste product of a still valid, higher priority choice, then you should proceed with extreme caution as change introduces new forms of failure. In other words, let it be. This can be disheartening at first, but is evidence of a highly functioning organization. Everything we do generates some kind of waste and there are probably bigger problems to address.

Now, should you find that the rationale behind the proximate decision is no longer true, or more likely that no one remembers/the decision was made by default, then your issue and its parent issues are ready to be prioritized for attention. I know, you really want to fix it, but all boats leak and it STILL may not make sense to fix it. If you do prioritize tackling the problem, a word of warning: false beliefs have a way of enshrining themselves deep in organizations and are surprisingly hard to yank out. As Carl Sagan warned us, it turns out this is why charlatans are so successful, because admitting one is wrong can be painful and we HATE cognitive dissonance. If you are aware of this, you can both avoid triggering resistance AND you can use discomfort with cognitive dissonance as a tool for influence. More on that in another post.

So far you’ve had it easy, as you can trace a problem back to a decision and merely have to do the very challenging work of updating everyone’s understanding of new facts, revising their understanding of cause and effect in interpreting those facts (their logic) and confirming that you are still aligned on the same outcomes. But what happens when your leaders intentionally did NOT make a decision? You’ve just gone from bad to worse. Still having fun?

In the very likely situation that your problem is due to an abdication of decision-making on the part of your senior leaders, you must exercise caution in the minefield of inter-executive politics. Indecision stems from one (or both) of two bad behaviors: a refusal to prioritize and/or a refusal to look at brutal reality.

If you are lucky enough to just have a CEO who hates prioritizing but not reality in general, who thinks you can do everything, then you have a shot. There are tools like the Coin Game, simple visualizations of the relationship between WIP and waiting, and others to break down the belief that starting more things means finishing more things. If those fail, you can use sequencing prioritization, like Christmas Prioritization, to avoid the pain of choice but help your company choose. Remember, when in doubt, reduce Work in Progress and prioritize at the constraint.

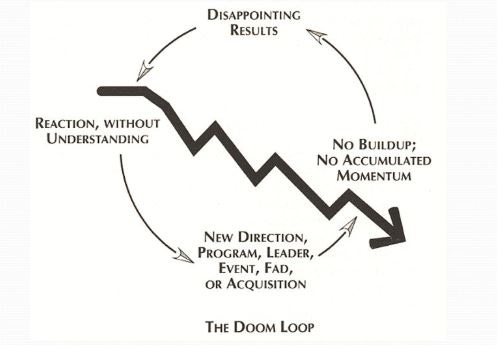

If your leadership refuses to confront reality, they will enter what Jim Collins coined, the Doom Loop in Good to Great, leading to the Five Stages of Decline in How the Mighty Fall.

Your responsibility, should you choose to accept it, is to make whatever you’ve discovered visible to get your leaders to look at reality. You must demonstrate that the problem exists, how it corresponds to poor performance in company goals, and how it stems from indecision. You must resist the temptation to place blame (you may only accept it), as blame will only generate further resistance. You can do this without heroes and villains, in fact you must. This is the part where you should risk getting fired by being a little forceful and working outside your box, because if you cannot get your leaders to look at reality, your business is going to fail, so you are going to lose your job one way or another. Besides, the decline isn’t fun to stick around for either.

So to reiterate– to solve a problem you must be willing to go to where it is, leaving your comfort zone or sphere of control. Second, you must confirm that a problem really exists, through clarifying the facts and their current relevance, the implicit organizational logic that led to a decision or indecision, and to confirm that the organization still wants the same outcome. All this just to agree that a problem exists. In the next part, we are going to use the same pattern, facts->logic->desired outcomes to avoid triggering defensiveness. But if you can pull all this off, building relationships, visibility and competence in your organization, then your career will progress to becoming an ill-informed, decision averse, reality denying senior leader yourself! Congrats!