If you’ve ever been in the part of the business that does the thing the business does as opposed to the part that convinces the outside world to buy what the business does (or the business itself) or the infrastructure that keeps any business running, then you’ve heard this phrase before. Usually you hear it from one of the other two parts of the business who don’t do the actual work of the business but think they do. And your eyes have probably rolled so far back in your head that things are still a little blurry.

But, they are kind of right. We’ve spent time on strategy, so let’s focus on the “getting stuff done” or preparation part of Strategic Preparation. As a quick refresh, the “stuff” that you want to get done stems from your mission, is clarified in your strategy and made specific in your goals. A Playing to Win-related article has a name for this connection between your goals and your daily work: capabilities.

What capabilities must be in place in order to execute?

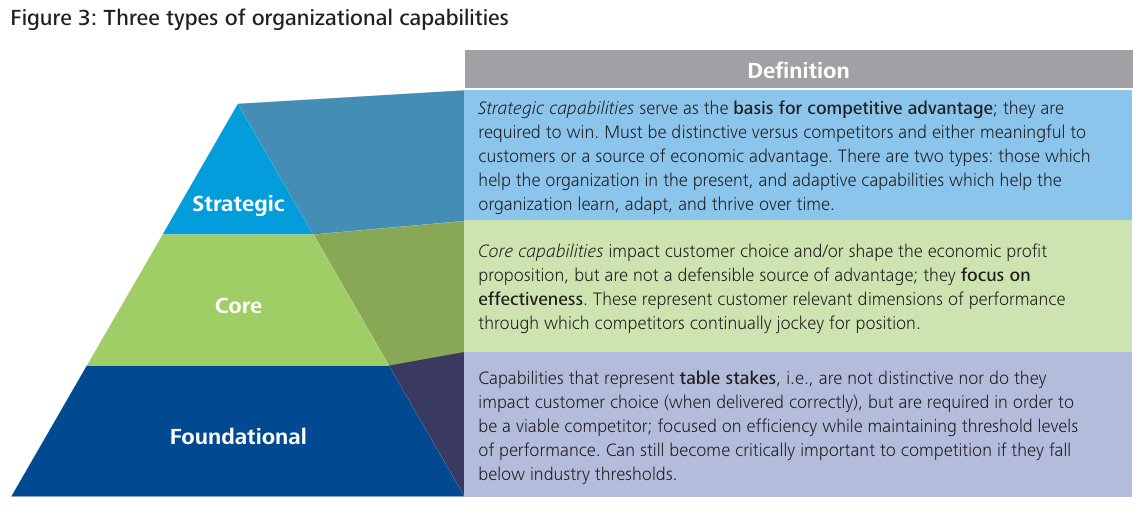

A capability is something your organization can and must do in order to succeed. Some elements are foundational, like paying payroll on time. Only the absence of such capabilities is noticed (and what makes early startups so painful for seasoned professionals). Core capabilities are those that describe the effectiveness of your product or service but don’t confer competitive advantage. Think of them as linear, but not exponential improvements over what is available in the market today. On-time flight performance is a core (yet surprisingly absent) capability from airlines. You won’t choose an airline strictly based on that criteria, but it certainly helps nudge you toward a given carrier for a given destination. Strategic capabilities are akin to the unfair advantage referenced in the Concept Stage. The things you can or will be able to do that no one else can, or cannot do so profitably. A word of warning to those who would become complacent: All capabilities shift down the pyramid over time. Elevators used to be strategic for tall buildings, now they are foundational.

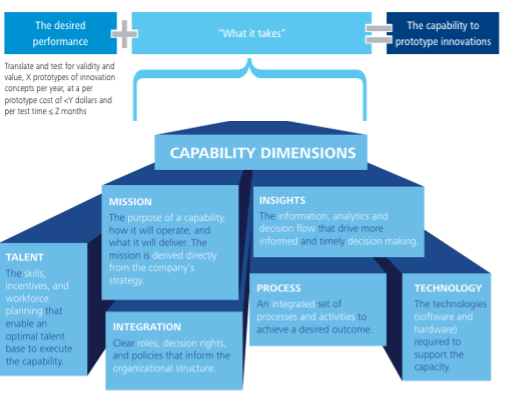

The idea of a capability may already exist in your organization, usually as a vague, unquantified description of activity or worse, someone’s name that usually does that thing. A classic example in healthcare services is “take great care of patients.” But capabilities have a stricter definition: They are the union of a quantitative description of desired performance (sounds a whole lot like a measure!) plus the work it takes to get there as detailed in the beautiful figure below:

Building your company’s capabilities is actually the process of iteratively defining your desired performance and developing the disciplined work process to get there. This pattern of setting your target before taking action shows up everywhere – we’ve covered it in measures, it comes up in test-driven software development, in sports, sales and everywhere people achieve what they set out to do. As the great Yogi Berra warned us: “If you don't know where you are going, you'll end up someplace else.” Given the time we’ve spent thus far in the Schutzblog on clarifying your desired performance, prepare to take the same disciplined iterative approach to the “what it takes'' work itself.

Let’s go back to our capability example to understand what it takes to build one:

“Take great care of patients”

Right in that little phrase are the parts of a capability, all vaguely defined. First, we have the “customer” of the capability: patients. Agile user stories implore us to keep the “user” of a capability clear in our minds, to access empathy, creativity and ensure that we build to a desired performance for the patients, not for our own fantasy. Stay grounded in the needs of your customers or get ready to create waste.

Second, “great” represents the desired performance measurement of the capability. You may immediately realize how unhelpful of a description “great” is. Perhaps better than “rude, inhuman and uncomfortable” which feels like the current standard of care. As you attempt to clarify the desired performance, prepare to debate and be dissatisfied with: Clinical outcome scores, participation rates, satisfaction results all as stand ins for “greatness” in care. The fundamental challenge of patient care is that we do not actually understand what it means to take care of patients in a generalizable way. This is not a commentary on style, bedside manner or experience, but rather that care is fundamentally chaotic and the desired outcome is dependent on initial conditions. There is no clear definition of “care” or “health” or “good” as much as we all want there to be as it differs for each of us and over time. Your responsibility, despite this chaos, is to reveal the measure of greatness in your particular product or service. Focus and disciplined iteration should get you there, but no one said it would be easy.

Finally, and most closely resembling what we may think of as “actual work” is the “take care of” phrase which maps to “what it takes” within the capability definition. What it takes are scores of people working in concert amongst uncertainty, complexity and variability. The challenge inherent to patient care is so great, that nothing makes me laugh harder than product companies in healthcare blindly pivoting into services, ignorant of the pain coming their way. The what it takes here are a combination of five levers in delivering a service:

Hiring the right people (and firing the wrong ones quickly)

Managing those people with direct observation and continuous feedback

Continually improving the work to be done: processes, protocols, etc.

Creating tools to support the work: equipment, software, job aids

Formal training of changes to existing employees and onboarding new employees

Each of these levers of a service capability is hard fought, as you can see, they are nested capabilities within the larger “take care of” capability. Each has its own defined performance, iterative discovery of what works, or cause and effect, and continuous improvement. And it never stops, because once you have mastered a level of performance, expect the goal posts to move.

The key takeaway from this entire piece is to remind you that it is okay to start vague with goals, with capabilities, with work descriptions, but your key job as a senior leader is to bring discipline and clarity to your organizational capabilities over time. Given this underlying challenge of operating a business while building/improving/fixing it, how can anyone possibly manage all of this work without everything grinding to a halt? Or asked differently from Playing to Win: what management systems are required?

From here the Schutzblog returns to what I wanted it to be in the first place: a series of framework snippets, aphorisms and tools that comprise the management systems built over the years of managing complex services backed by complex technology, which I call Strategic Preparation. The theoretical framework is based in Agile, DevOps, Strategic Choice theory, OKRs and, believe it or not, clinical medicine. Stay tuned!

Great timing for me, Andrew! Thanks as always.